Breaking Point: the emotional toll of top-level tennis

Many tennis players struggle to contain their emotions on the court. What is it about the sport that provokes rage?

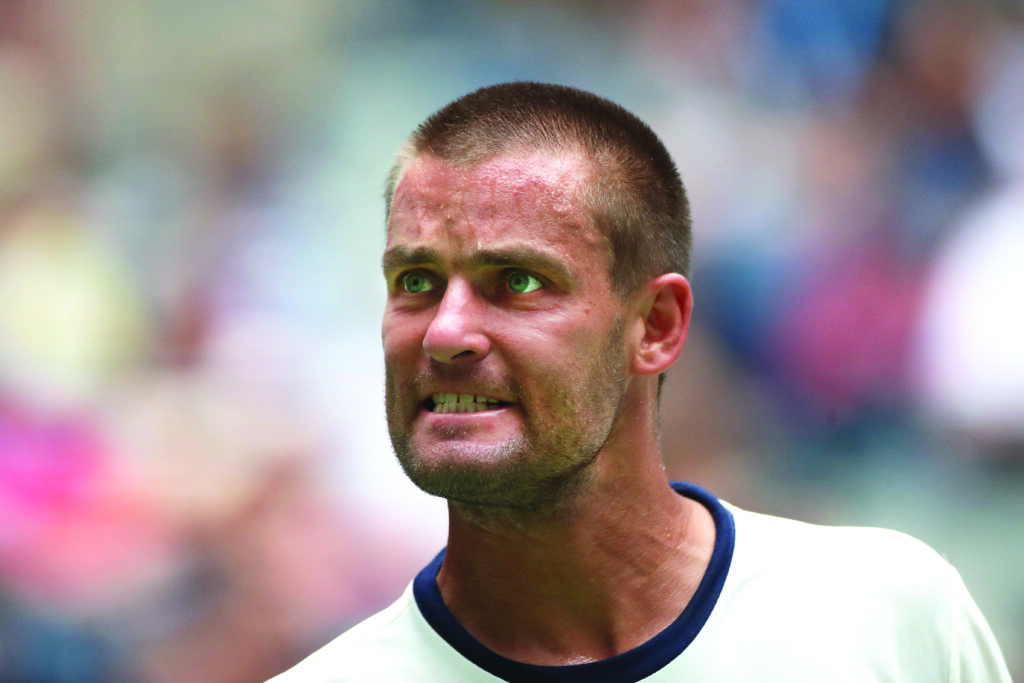

IN THE THIRD round of the 2008 Miami Masters, Russian tennis player Mikhail Youzhny turned his racquet on himself. With the match locked at one set apiece and his opponent, Nicolás Almagro, attempting to serve it out at 5-4 in the deciding set, Youzhny forced break point. A long and gripping rally followed, before Youzhny hit a tired backhand into the net. As he walked back to the deuce court, the Russian began berating himself, before repeatedly smashing his racquet into his forehead, eventually drawing blood.

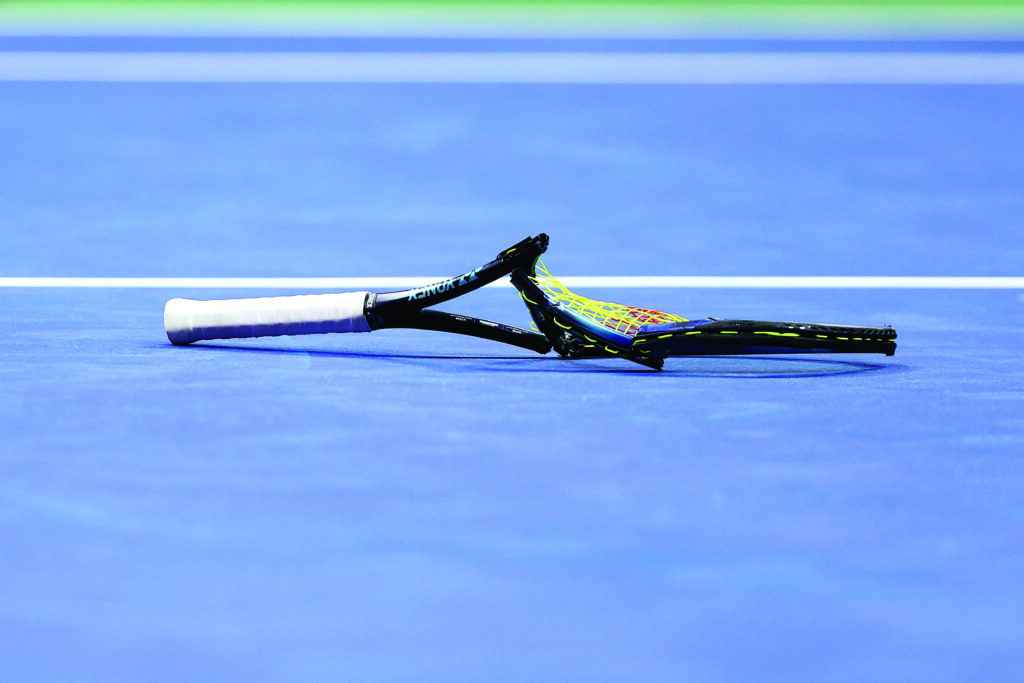

Youzhny’s act of self-flagellation was perhaps the most pointed display of emotion ever seen on a tennis court, though admittedly, it’s a crowded genre. Type ‘tennis tantrums’ into Google and you’ll find countless examples of players losing it on court – some, like John McEnroe’s 1981 howl of fury, “You cannot be serious”, have even entered the cultural vernacular. Normally, it’s players’ racquets that end up worse for wear, or an umpire or linesperson who bears the brunt of their frustration. In the case of Youzhny, who would go on to win the match, his anger was directed at the most appropriate target: himself.

Of course, volcanic displays of emotion are not unique to tennis. Athletes in all sports lose their temper, mostly at opponents and referees. In tennis, however, rage is often self-directed, the effect of an emotional outburst both concentrated and amplified by the game’s solitary nature and the stage the court provides. The sport’s strict rules and courtly traditions don’t help either, creating a smothering, even claustrophobic atmosphere.

Former Wimbledon champion Pat Cash likens the court to a colosseum. “You’re going out there and it’s a funny balance between sport and entertainment,” he says. “It’s a gladiatorial sport.”

That sentiment is echoed by Michael Lloyd, national psychology manager at Tennis Australia. “I’ll often say to people that elite sport is almost like the ultimate form of reality TV,” says Lloyd, who’s speaking to me from his office overlooking the 4500-seat Pat Rafter Arena at the National Tennis Academy in Brisbane. “There’s a real appeal for people in saying, ‘I want to be able to come and watch someone ply their trade, display their skills in front of an audience, doing something that, one, I’m not physically capable of doing, and two, I don’t know if emotionally I could do or tolerate that level of isolation and exposure’.”

But if the court provides the stage for drama to unfold, it’s worth looking at the factors that push the game’s protagonists to the point of psychological breakdown. Because the worst-kept secret in tennis is that mastering, controlling, processing and even deploying emotions is the game within the game. And in this contest, ‘love’ isn’t really part of the calculus.

CASH RECALLS ONLY one occasion when he really lost it on the tennis court. It was when he was 18, playing at the 1983 US Open against American Bill Scanlon, who had the crowd behind him. “The crowd was going crazy,” says the 59-year-old, who’s speaking to me from his home in London’s Chelsea, a base for his work as a commentator and consultant coach on the ATP tour. “I got bad line calls. It was just one thing after the other.”

It wasn’t long afterwards that Cash began working with former head of sport psychology at the Australian Institute of Sport, Jeff Bond, who in their first meeting, emphasised the importance of emotional mastery, while also underscoring its elusiveness. “He got a piece of paper, he drew a line and he said, ‘Right, this is where we want to be emotionally. But it’s near impossible, so you’re going to go up and down, up and down. What we want to do is keep those ups and downs as small as possible.’”

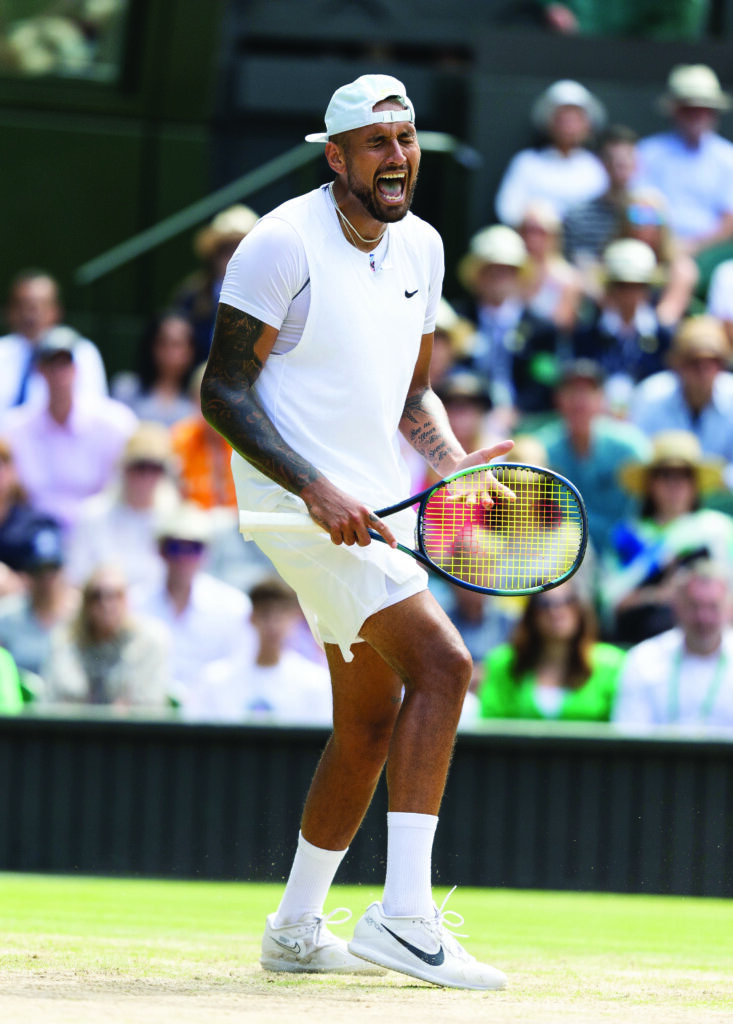

In hindsight, Cash believes his temper didn’t lose him many matches. “Often, you’re just not playing well and that’s why you get upset,” he says. It’s when you’re playing well that unchecked anger can cost you, he adds, citing Nick Kyrgios’ flameout in the 2022 Wimbledon final against Novak Djokovic as an example of a player letting his frustrations derail him. “Nick was playing superb tennis, and he just had a meltdown in the third-set tiebreaker, and then that was it,” says Cash. “He was just sitting down at the change of ends and screaming. I was sitting there horrified, going, What is he doing? He’s blowing himself up. He’s shooting himself in the foot.”

This is what unbridled emotion can do to a player’s fortunes. Indeed, it’s the ability to process and work through the constant and cumulative frustrations the game throws at you that separates the truly great players, Cash believes. “Federer and Nadal, all the greats, anybody who’s got a Grand-Slam title under their belt, is a really, really good problem solver on the court,” he says.

They must be, for tennis, by nature, is a game of mental attrition. Consider Roger Federer’s recent comment during his commencement address at Dartmouth College, that while he prevailed in 80 per cent of the 1526 singles matches he played in his career, he won a mere 54 per cent of the points in those matches. It’s a statistic that underlines how competitive and cutthroat the game is at the elite level.

This dynamic puts players on an effective war footing with their emotions. As such, the battle to stay in a positive, focused state of mind and not to let minor irritations distract you from your game plan is pivotal to success.

“There’s so many different elements to the little battles inside the war,” says Cash, citing preparation, game-planning, injuries, nerves and the pressure that comes when you find yourself on the back foot – facing a break point, say – shortly after walking on the court.

“Within five minutes, you can find yourself under pressure, knowing that a bad start could cost you a set or potentially the match.” Your opponent, of course, must fight those same mini mental battles. But rather than being an abstract figure you can demonise or keep at arm’s length, in tennis, it can feel like your opponent is breathing down your neck.

“You’re in the locker room next to your opponent,” says Cash. “In boxing, they keep you apart. In MMA, they keep you apart. In tennis, you see the person all the time. At breakfast, warming up. And that’s before you get on the court.”

With so many pressure points, it doesn’t take much for things to fall apart. And the problem is, when they do, you’re largely on your own.

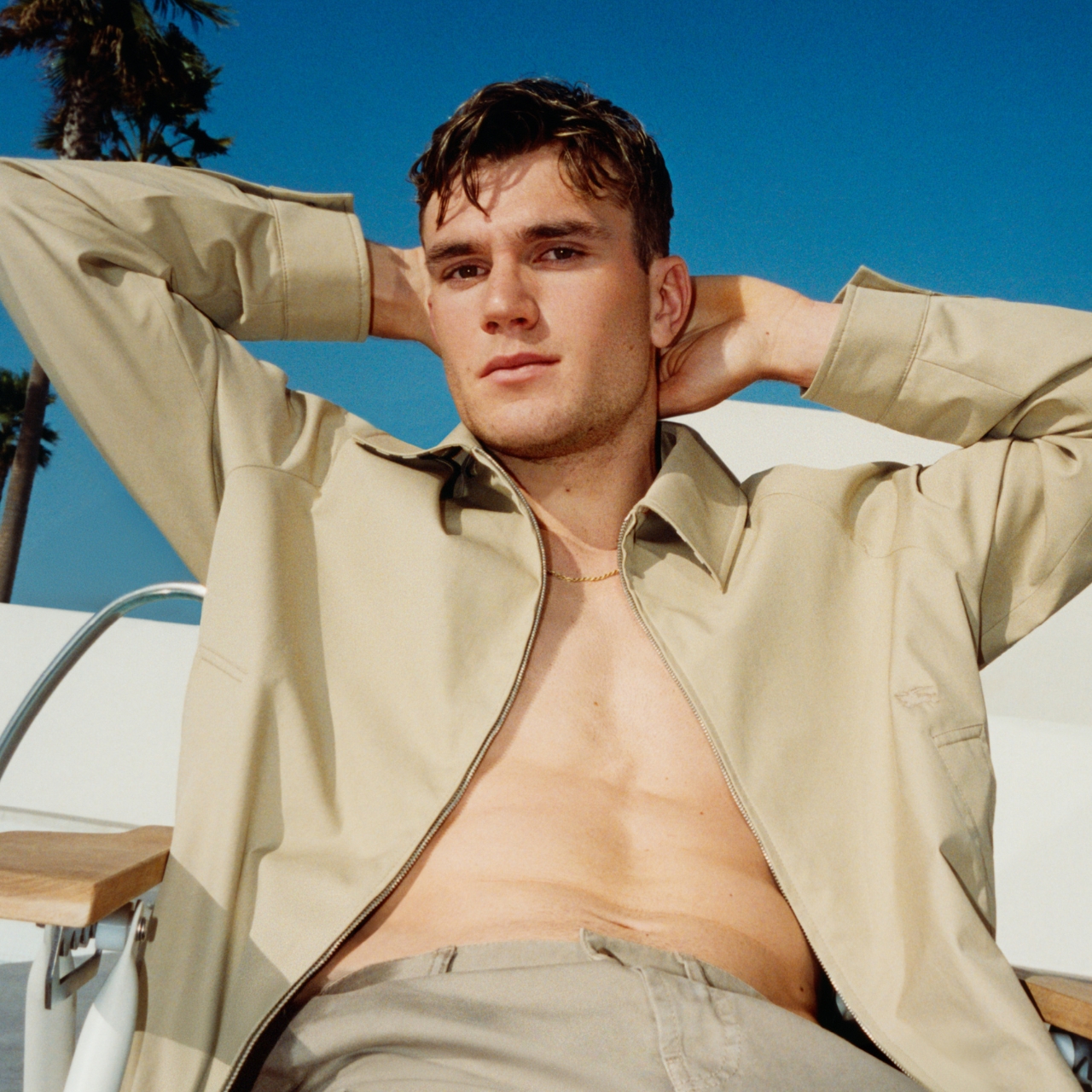

WITH HIS STILL boyish, dare we say, choirboy looks, Todd Woodbridge doesn’t strike you as a player who would’ve struggled to control his emotions on the court.

“No one sees me like that,” laughs the 53-year-old media ambassador for Tennis Australia, who was one half of multiple Grand Slam-winning doubles pairing ‘The Woodies’, with compatriot Mark Woodforde. “Even less so nowadays. But I very much relate to how Nick Kyrgios feels out on court, and I find it fascinating that Nick feels like he’s the only one.”

Once you’re on the court, Woodbridge says, your emotional equilibrium is challenged by the fact that tennis is demanding both physically and mentally, the two facets of the game locked in a symbiotic embrace. “What happens within that is that there’s accelerated heart rate, there’s huge amounts of adrenaline, and when those come together, you find that it is very hard to stay calm. Very few people are really able to do it.”

Woodbridge likens adrenaline spikes to having a high-blood-pressure issue. “There’s a smothering feeling coming over you,” he says. “Because what tends to happen is that, as you fatigue, you’ve got less time to recover, you start to panic, you start to go away from your game plan, you start to hit shots that are low percentage, then that becomes frustrating, and so the momentum builds to where you see somebody, as I like to say, lose the plot.”

Kyrgios – a fascinating case study in emotional volatility – is an outstanding player when he’s able to manage his adrenaline, Woodbridge says. “When he can hold that adrenaline and keep it at, let’s say, 70 per cent, that’s when he is mentally good,” he says. “As soon as that gets in the 80s and 90s is when he loses it, and then he’s struggling to win matches.”

In the pre-Hawk-Eye era, a bad line call was usually the trigger for a player to explode. These days, it’s often an accumulation of minor frustrations. The problem for the singles player is that, in such situations, you have no one to turn to for help.

“When I had a [doubles] partner, I was able to talk tactics,” says Woodbridge. “As soon as you do that, you release a bit of your pressure and stress, and you’re not internal anymore. When I was playing singles and struggling, you can’t verbalise outwardly. I would internalise everything and that was disastrous. You’re fighting yourself.”

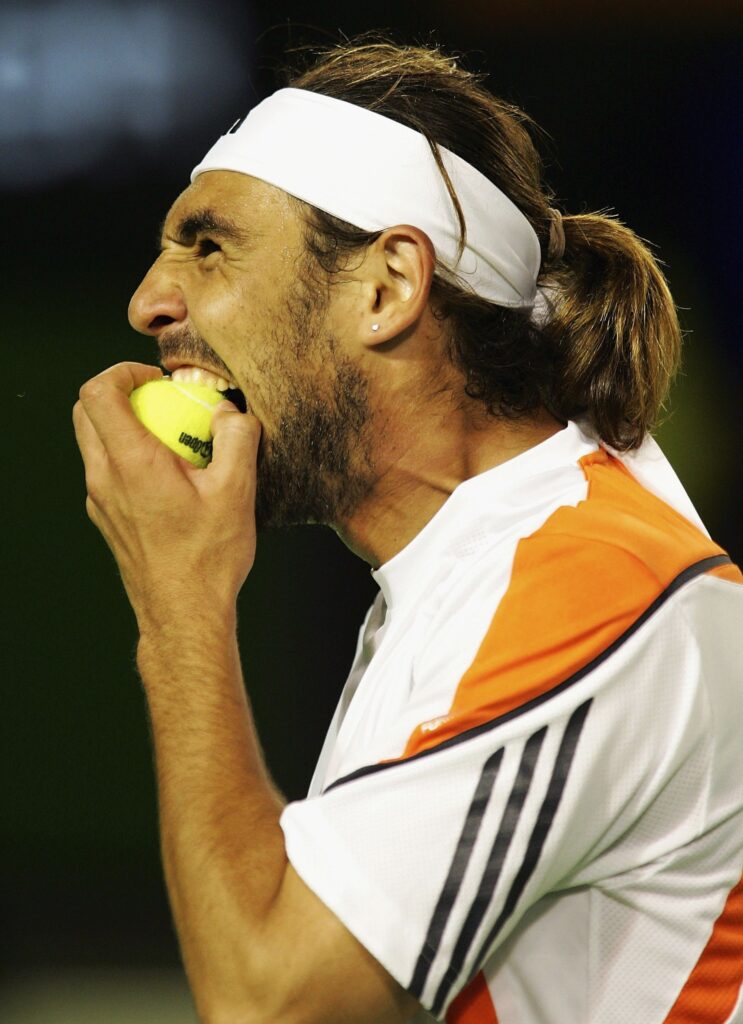

TO WATCH CYPRIOT Marcos Baghdatis smashing racquet after racquet (four in all, some of them still in their wrapping) at the 2012 Australian Open was to wonder what could possibly be going on inside his head to cause such sustained fury. In that moment, the answer was likely pure red mist, later followed by embarrassment. But you do have to wonder if there aren’t underlying factors driving these kinds of outbursts.

A tennis player represents a particularly complex challenge for a sports psychologist. Playing tennis for a living is not made any easier by the oppressiveness of the game’s cut- throat win/loss dynamic, which can have a corrosive effect on a player’s mood and deeper mental state.

“The tour is brutal. It’s week to week and unless you win the damn tournament, you’re depressed at some stage of the week,” says Cash. “If you’re a psychologist, you’d be going, ‘Oh no, this job’s not good for you, buddy. You’ve got to get another job. What the hell is this sport?’”

Someone who might know is Dr Tom Ferraro, a sports psychologist from Long Island, New York, who’s been working with tennis players for more than 30 years. At the root of many players’ emotional difficulties, Ferraro believes, is a tendency towards perfectionism. It’s something to which those who’ve reached the pinnacle of their sport are particularly susceptible. “Perfectionism is a problem where the athlete’s actually expecting not to make any mistakes,” he says. “They don’t know that they’re processing things that way, but that’s what the reality is.”

Where does perfectionism originate? Ferraro points to childhood dysfunction – see Andre Agassi’s Open for a first-hand account of what that might look like. “The cause is very frequently about an underlying low self-image that starts when you’re very young,” says Ferraro. “You’re not attuned to properly by your parents, so you wind up feeling shameful or empty. It’s devastating because what happens is you have chronic anger almost all the time, because you’re making small mistakes all the time.”

This is a particularly acute problem in tennis, a game ruled by millimetres and one in which ‘errors’, both forced and unforced, determine the outcome of a match and are highlighted on the scoresheet. “If you’re constantly angry at yourself, eventually it’ll break your defences down and you either act out with some crazy rage or you fall into despair,” Ferraro says.

The need to manage constant disappointment is perhaps why psychological strategies across sports draw on Stoic principles of resilience and self-control, Cash believes. “It’s not the emotions that are the problem, it’s the reaction to the emotions,” he says. “An emotion only lasts, I was taught, about 90 seconds. It’s if you hang onto it that it can last a lifetime. But the actual physical feeling doesn’t last very long.”

Of course, unlike, say, football or basketball, where you need to get on with the next play almost immediately, tennis gives players ample time for rumination between points. These pivotal moments can open a potentially lethal mental chasm, one that players rely on rituals, routines, key words and visualisations to bridge. “The beauty of the contest in tennis is, it’s very much stimulus and response,” says Lloyd, who points out that over the course of a tennis match, the ball is typically in play for only 15-20 per cent of the time. “So often the greatest competitors are not only the ones who bring the great game, they’re those who manage themselves best the other 80 to 85 per cent of the time.”

At this point, it is worth asking if anger is necessarily a negative emotional reaction. After all, isn’t it a natural and logical response to a challenging situation?

“Anger is a very powerful tool,” confirms Cash, who throughout his career used it as a force for motivation. “It’s when it boils over to being destructive that it becomes a problem.”

Lloyd agrees, pointing out that emotions need an outlet, lest they curdle. “Some form of release can be an important aspect of the self-regulation that allows us to continue to perform at our best. You’ll often see players give themselves a slap on the leg, something like that, because the emotion has to go somewhere. It’s part of that internal battle.”

Of course, there will always be outliers. McEnroe, most experts agree, was the exception that proves the rule that unchecked anger hampers performance. “He [McEnroe] is the only one who could get really angry and then come back and the next ball start playing well,” says Cash.

And then there are the big three – Djokovic, Federer and Nadal. It just might be that the three greatest players in the history of the game have been the most adept at controlling and modulating their emotions to benefit their performance. “They’re always playing games with themselves to try to find that space where they are able to be free,” says Woodbridge. “That’s what I find extraordinary when you watch what Nadal’s done over the years, and what you see Novak do. He’s far better than anybody else at controlling it [his emotional temperature], bringing it back. What he does is he controls the court, not just his end. He’s very good at changing patterns of play. Or if he goes flat, you see him use the crowd. He finds a hate moment with a spectator, a moment that’s able to change his adrenaline.”

That this level of emotional calibration is beyond most players is hardly surprising. But while the best might hide it better, the game’s mental toll spares no one. Indeed, as explosive as players’ tantrums can sometimes be, for those who prevail on the court, there’s often a commensurate outpouring of joy mixed with relief. Recall Djokovic’s screams of ecstasy as he fell to the court and ripped his shirt apart after outlasting Nadal in a five-set, five hour-and-53-minute epic in the 2012 Australian Open final. In such moments, the immortal words “Game, set and match” are not just a declaration of victory; they also signal a respite from an emotional odyssey.

Related: