The Beatles will never die. Is that a problem?

News that Sam Mendes will helm a four-film series on each member of The Beatles raises some questions about cultural fatigue, the power of nostalgia and the complexities of generational identity

I HATE TO say it, but ‘The Beatles’ has proved to be an ill-fitting name for the most successful rock band of all time. ‘The Cockroaches’ might have been a better fit, for culturally at least, the Fab Four are never going to die.

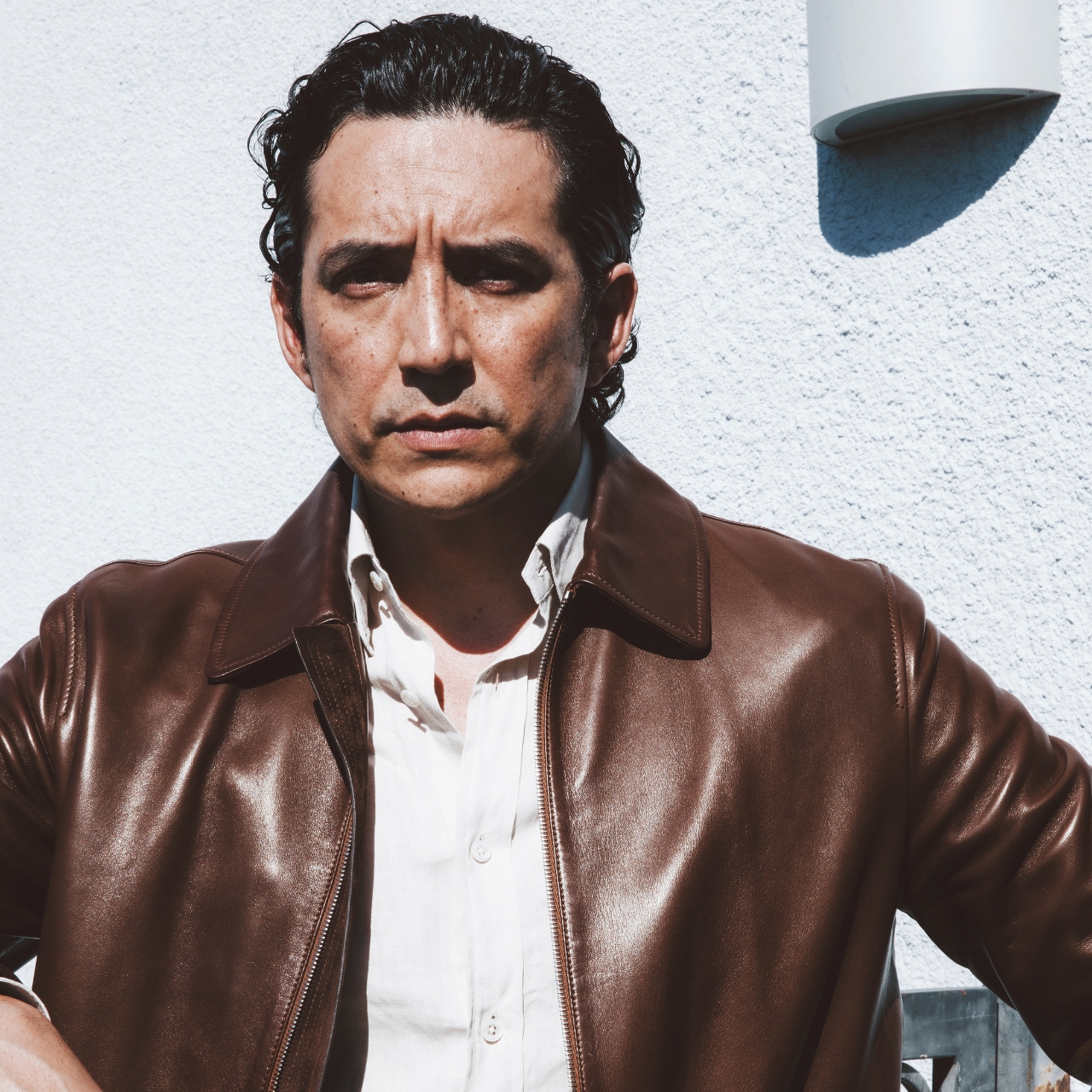

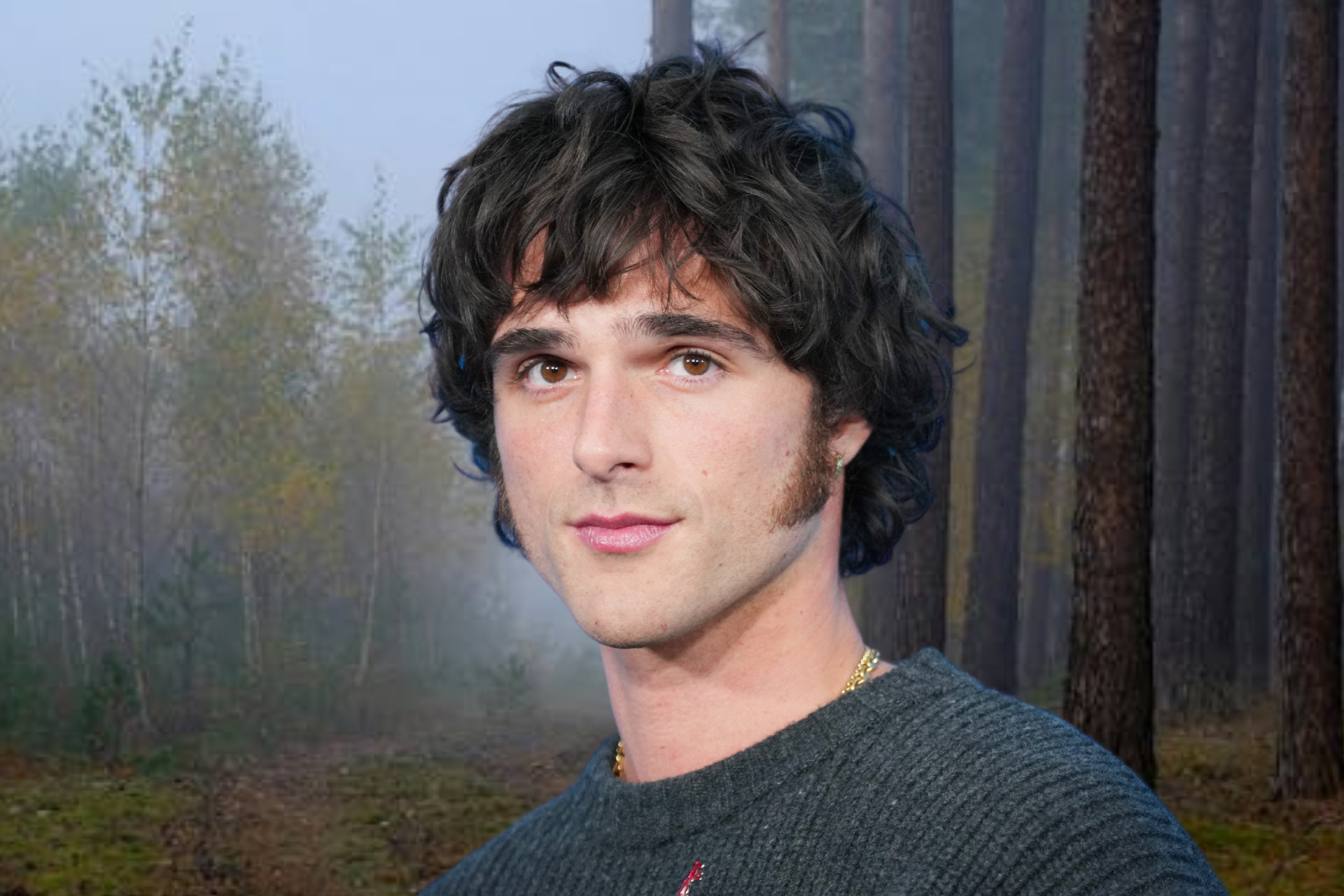

This week it was announced that director Sam Mendes will be making four biopics (a quadrilogy) on each of the four Beatles – John, Paul, George and Ringo. The films will star internet boyfriends (who may object to that term but nevertheless), Harris Dickinson as John Lennon, Paul Mescal as Paul McCartney, Joseph Quinn as George Harrison and Barry Keoghan as Ringo Starr.

The project is the latest in possibly the most successful cultural cottage industry of all time: Beatles ephemera. It’s an industry that trades on nostalgia and spans the gamut from unearthed recordings – most of these were ‘earthed’ for a reason – documentaries, like 2021’s genuinely fascinating The Beatles: Get Back by Peter Jackson, umpteen re-releases and digital remasterings of albums, stage shows, musicals, merch, and now movies. All this for a band that had teenage girls screaming in hysterics over 60 years ago.

As a Gen Xer who grew up listening to my mum’s one prized Beatles album, ‘The No.1s’, I’ve always had an interest in the Fab Four. I’ve read a few of their biographies and remember watching the seminal six-part doco on the band, The Beatles Anthology, which was released with the previously unfinished John Lennon song ‘Free as a Bird’, in the mid ’90s.

But even as a fan, I found myself greeting news of the new films with mixed emotions. I was excited by the cast, particularly Mescal as McCartney. I’m happy that the band’s legacy will live on and that their music is now likely to be streamed incessantly and their fashions and haircuts appropriated and commodified. But I also found myself nursing some curious feelings, ones that have become increasingly common as I get older.

I wondered, yet again, whether pop-culture is eating itself – to be honest, it should have keeled over from indigestion long ago. I also felt some level of frustration that for many young people who don’t really know who The Beatles are and what they meant to previous generations, these movies will be their introduction to them, rather than the music of the band itself.

Cultural ignorance and its even more concerning sister phenomenon, cultural blackholes (you’re kidding, you’ve never seen Star Wars!), are one of the less acknowledged but very real realities of aging and living in an age of myriad, splintered entertainment choices. I have found myself sighing (always internally) when ‘younger people’ – this is the first time I’ve used this odious phrase in a column and its implication is deeply unsettling – have, quite understandably, professed that they don’t know who an artist or actor from yesteryear is. They don’t appreciate how big a star that person was in their heyday, and they don’t really understand why a film is being made about them.

It’s similarly frustrating when an old film or TV show is remade, and you, as the designated older person, have to point out that it’s a remake – they should know that! you think to yourself. You might then add, if you’ve been caught on particularly bad day, that the original is untouchable and the new version can’t possibly live up to it.

Again, the prevalence of movie remakes raises questions about the lack of original ideas in the contemporary entertainment industry, though, to be fair, many stories you might assume to be wholly original often have their roots even further back in literature, or even in myth – Star Wars, for example drew inspiration from Joseph Campbell’s theories on the ‘hero’s journey’. There are no new stories, just new angles, stars and packaging.

Why is this ignorance so frustrating? It’s perhaps because pop-cultural touchstones have played an outsized role in shaping generational identity, from Boomers onwards. This is particularly true, I would argue, of Gen X and Millennials – the VCR/DVD generations – who rewatched movies incessantly and grew up in an age when music videos had a cultural primacy. The movies, shows and songs from these eras defined our childhoods and teenage years and inevitably provoke nostalgia, an immensely powerful force.

As such, a blank look from a younger person when you mention an artist or actor whose poster once adorned your bedroom wall can be taken as an affront to your identity. It says things you cared about don’t really matter, that they are no longer culturally relevant, which by extension, means you are no longer relevant. Most damningly, it tells you that you’re old.

This reaction is, of course, hypocritical. Older generations than mine undoubtedly shook their heads at me when I professed that I couldn’t understand how a hairy, out-of shape-by-today’s standards Burt Reynolds could possibly have been regarded as a sex symbol in the 1970s. Or that the now decrepit Warren Beatty was the original George Clooney (himself now rather craggy). Those things are largely incomprehensible to those of us born later, bringing to mind the quote from L.P. Hartley in his 1953 novel The Go-Between, where he wrote, “The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there”.

Similarly, while I might shake my head that a younger person has seen Top Gun: Maverick before seeing Tony Scott’s original testosterone-fuelled campy confection, Top Gun, I often have no idea who artists they listen to are – I was shamed in the office last year for not knowing the lady standing next to Taylor Swift at the 2024 Superbowl was Ice Spice – or why Mr Beast is famous. On contemporary music, in particular, I am increasingly out of touch. The difference is that my ignorance is expected, and probably preferred, lest my affiliation taints their fandom by making it seem daggy.

Some forms of entertainment do endure better than others. Music, in its purity and universal, perhaps even biological appeal, is more culturally resilient than film or TV. This is perhaps due to the influence of fashion and style and the advancement of technology, meaning movies and TV series are often time capsules for the era in which they were made. I personally find it difficult to watch a black and white film with one static camera angle from the fifties, for example. Similarly, the baggy preppiness of clothes on ’90s shows like Friends and Seinfeld, for example, can appear horrifyingly dated today. Fashion, though, has a unique and ingenious ability to repurpose looks in ways that make them cool for today’s youth – again this could be an example of cultural cannibalism, or it could just be fun.

And that’s possibly the deeper truth here. For while pop culture is often reductive and recycled, it doesn’t stand still. It’s possible these Beatles films will find a way to add to the band, and particularly each member’s legacy. Heck, it’s possible the films will be regarded as ‘new’ classics and even be remade themselves one day.

So, I will watch The Beatles biopics – yes, even the Ringo one – because it’s possible I might learn something from them. That speaks to the fact that we are all cultural ignoramuses and blackholes to some degree. Taste is both personal and hive minded. We are defined as much by what we choose to listen, watch and increasingly search, as what we don’t. But pop culture moves on, with or without us.

Related: