Justin Williams on making art: "sometimes, it just needs to be painted"

Justin Williams is one of the most significant Australian figurative painters working right now, with serious collectors all over the world buying up his works. Still, he insists he’s no good at painting. “I’ve just become obsessed with it and now I’m too old to stop”

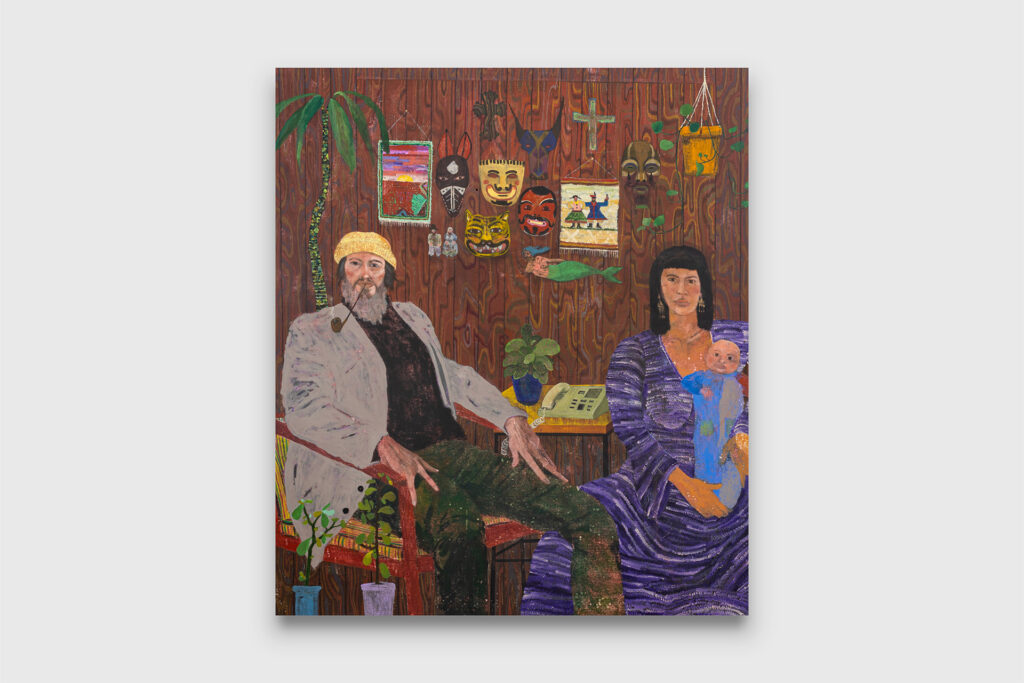

JUSTIN WILLIAMS IS standing in front of a 1.88 x 1.62-metre painting titled All the objects in the world won’t make that phone ring (2024). In it, a gentleman is smoking a long, skinny pipe; his fingers are equally, eerily slender. Next to him, with a baby in her lap, is a dark haired woman wearing a purple dress. Hanging from the wall behind them are masks, woven tapestries, a religious cross and what appears to be the carving of a mermaid. Heaving with colour and life, there’s a lot about the painting to take in. But a few weeks ago, it looked completely different.

“This was actually a big window to an outside scene, and there was a man milking a goat,” says Williams, gesturing to the area behind the masks and the mermaid. “It came from this story of my grandparents. Their baby, Glen – my uncle – had a really bad stomach when he was little, so he had to drink goat’s milk formula.” (Glen, Williams explains, is the baby in the painting.) “For some reason, instead of just buying goat’s milk formula, my grandpa bought an actual goat and tried to milk the goat. Then the goat ate some stuff that was left outside, I think it was washing, and. . . it died.”

Looking at this painting – and many of Williams’ works – you’d never guess it was inspired by such a peculiar yet quotidian story. There’s something mystical about the subjects he paints, the clothing they wear and the postures they assume; it’s difficult to pinpoint whether the worlds they occupy are contemporary, or from another time. Williams likes that ambiguity, and says his subjects are just as likely to be informed by an interaction with “a random weirdo on the street” as they are a biblical reference, like Joseph and his technicolour dreamcoat, or the tale of a Bedouin who sucked poison out of a snake bite his grandmother received as a child (this actually happened).

“If I spend too much time planning it out, then there’s not enough openness to accidents,” says Williams of the way his canvases shape-shift from start to finish (he had intended to include a painting of a scene from the birth of his daughter in his most recent solo show, but decided to shift to a more bohemian ‘waiting room’ scene when it wasn’t feeling right). “It’s not like, This has to work. Because if it doesn’t work, it doesn’t. It’s about having a trust that the art knows more about what it’s doing than I know about what it’s doing. Having an idea for a narrative, or a story, and then leaving it open. The paintings are like a mix of present and past, without it being like pure abstraction and not making sense. But . . . how we think doesn’t really make sense.”

He glances back at the painting of the couple, then turns back towards me and grins. “Am I making any sense?”

This month, Williams held a solo show at Sydney’s COMA, a contemporary gallery with a roster of young yet in-demand Australian artists making names for themselves on the world stage. Titled ‘Waiting for Lavender’, it marked a homecoming of sorts for the artist – Williams has shuttled between Santa Fe, New Mexico, and Paris, France for the last three or so years; in the last two decades, he’s spent more time living abroad than at home. During this time, Williams, who grew up at the base of Victoria’s Dandenong Ranges before moving to the Surf Coast, has held solo shows at highly respected commercial galleries, including Roberts Projects in LA and FORMA in Paris, where, in 2024, his works were exhibited alongside (and curated in dialogue with) those by Belgian painter James Ensor and French symbolist Paul Gauguin. He’s also shown at Art Basel Miami Beach, Dallas Art Fair and Sydney Contemporary, where he’s a main attraction at the COMA booth.

Such was the interest in ‘Waiting for Lavender’, Sotiriou was able to raise Williams’ prices, with larger works commanding up to $65,000. Close to half the paintings sold before the show even opened, with the majority selling before the show’s conclusion on February 22. While some went to overseas collectors who’ve been following Williams’ career for years, Sotiriou says there was a pronounced uptick in interest from local buyers, who are typically more conservative.

“Justin’s style of painting isn’t faddish at all,” remarks the COMA founder, reminding me that unlike some flavour-of-the-month painters, Williams didn’t have “this psychotically quick and unhealthy rise”. “It’s been really measured; he’s had this amazing, steady growth. So he’s a really great investment, because he’s never hit a dip. He’s got a consistent market, rather than a strange, speculative, bubbly market.”

It was the rich layering of influences that first endeared Sotiriou to Williams’ work, and this melting pot of colour, culture and historical references – often peppered with winks to his favourite artists and art periods – is what draws so many fans to his work today. The grandson of Egyptian immigrants, Williams’ heritage flavours everything he paints, as does his experience as an ‘outsider’, which stems from his childhood growing up in a white, middle-class community with ethnic relatives on his mum’s side and convict blood on his dad’s.

“I never really felt connected to the groups of people I was in,” explains Williams. “I was always embarrassed by my mum’s side growing up. I just wanted to be this normal Australian dude.” That feeling of outsiderdom continued into his twenties, when he was unable to get into fine arts programs at any of the Australian universities he applied to. “I had a bit of a chip on my shoulder because of that,” he says with a gentle shrug. “Maybe it was looked at as a negative when I didn’t get into those kinds of courses. I was a bit lost, and everything felt a bit closed-off in Australia. ‘Cause if you didn’t get into a good fine arts degree, then the commercial galleries wouldn’t show your work. But it really gave me a chance to feel like things were more open. I didn’t get in, so I had nothing to lose.”

It wasn’t until he moved to New York that Williams realised the academic route probably wasn’t for him anyway, and that beyond Australian borders, once you began producing work, no one really cared. So he started assisting experienced artists – which he describes as being “more like an apprenticeship”. “It was old school, like you’d go and learn a trade in a way . . . I realised I’d rather learn from someone how to stretch a canvas, what material to use, what the pigments are made out of. I mean, I’d rather learn about the egg tempera technical aspect of how to paint the frescoes in Pompeii from some nanna who’s just learned how to use YouTube.”

While working for other artists, Williams was establishing his own visual language. Cults and eccentric figures were an early preoccupation – Williams had grown up not far from the Victorian lakeside town of Eildon, where The Family, a doomsday cult led by Anne Hamilton-Byrne, was based; another figure from his childhood, Baba Desi, a self-proclaimed ‘wizard’ whose rejection of modern society manifests in colourful robes and handmade staffs, is one of the recurring figures in Williams’ works.

“Early on within the work I was exploring a lot of themes of cults and myths, weird people on the fringes of society. But it all came back to . . . almost autobiographical portrait work. And I’m like, Okay, it’s about me. I’m an outsider and I’m drawn to these people for that reason. And I don’t mean in terms of ‘outsider art’, because that carries a whole different context. It’s more to do with how I felt growing up and where I’m from. I always felt like I was outside looking in.”

When Williams began exhibiting his works, they were heavily layered, the grooves of his paintbrush sweeping oils across the canvas visible to the onlooker. His figures were also more abstract, but his ideas and influences were rich. “He has this little maelstrom around him,” recalls Sotiriou, of coming across Williams’ work for the first time. “Essentially, that meant he’d become a great painter. There was too much input for this dude not to come out, at least at some point, on the other side, with something really exciting.”

Not long after his first COMA show, Williams decided to experiment with a new technique, or “treatment”. He started to sand back his layered canvases so that the paint on the surface appeared thin, as though stripped by age. “It basically destroys the whole painting,” remarks the artist. “And then I’ll build certain aspects of it back up, or maybe I’ll redo the entire painting . . . I tried to learn how to paint like the masters, then to ‘unpaint’, so that they looked naive.”

At the same time, his figures became more figurative, but rather than trying to achieve photographic levels of likeness, he leant into the awkwardness of mistakes, developing what art critics would come to label his signature style. From that moment, things began to click. “This hand is a great example,” he says, pointing towards a man clutching a mug in a work titled It’s me really doing that to someone else (2024), which also appeared in Waiting for Lavender. “This guy’s hand, there’s no thumb; it’s just like pointy weird fingers. But no one cares. It’s like, that works. It’s a hand. But it’s without making it feel contrived. I think when style fails, or it doesn’t get across, or it seems immature, is when that hand is on every painting, and you are the guy that does no thumbs. If you try for a style, it’s never gonna become a style.” He interrupts himself to establish that in no way is he “an original, or one of a kind”. “If you think you’re an amazing painter or artist then you’re probably your own worst enemy.”

“I’m awkward, and it’s [about] portraying an awkward sensibility within the people that are in the works.”

The funny thing about Williams is that while he presents as a regular dude without an elitist bone in his body – the kind of guy you might enjoy a smoke with while checking the surf at Torquay – his knowledge of art history is immense, and he certainly thinks about the space he occupies within the arts world. But his everyman demeanour draws a younger generation of art fans towards his oeuvre, just as much as it does established collectors with a trained eye for the next big thing. Both demographics flocked to the opening night of Waiting for Lavender, which was so well-attended (around 550 people made the trip to the gallery’s new warehouse space in the industrial streets of Marrickville), it spilled out of the gallery, onto the street and into the summer night outside.

Williams was overwhelmed by the response, because for so many years, the Australian arts establishment had been sluggish to show interest in his work. “When Australian museums were buying hot young Australian artists and we were trying to get them to buy Justin Williams works, they were like, ‘We don’t really know who this guy is’,” recalls Sotiriou with the knowing grin of someone who liked something before it became cool. “But while that was happening, huge collectors overseas were starting to buy Justin Williams in depth . . . Collectors are seeing him as one of the most significant voices in figuration in Australia.”

In the wake of his homecoming show, the local establishment appears to have changed its mind, with a major Australian public museum that cannot yet be revealed acquiring a large painting by Williams.

The title Waiting for Lavender was literal – the majority of the works in the show were painted while Williams, who is 40, and his wife, Jade, waited for the birth of their daughter. But the symbolism of the narrative extends even further. For Williams, someone who never saw himself settling down into a conventional life, the show represents a moment of arrival.

“I went to see a tarot [card] reader last time I was in Paris. She was like, ‘You can either die when you’re 50, or you’ll go on a different path where you’ll find love and you’ll have a different trajectory, but your art will have the same impact’. And I was a bit worried. Would it kill my work in a way, being normal?” he wonders aloud. Glancing around COMA, it’s clear the answer to that question is ‘no’. “I mean, it’s not like I’ve been gifted, or touched with something special or magical. It’s just that I’ve been dumb enough to keep painting, and now it’s what I do,” he says with a chuckle. “I’m not that good at painting; I’ve just become obsessed with it and now I’m too old to stop.”

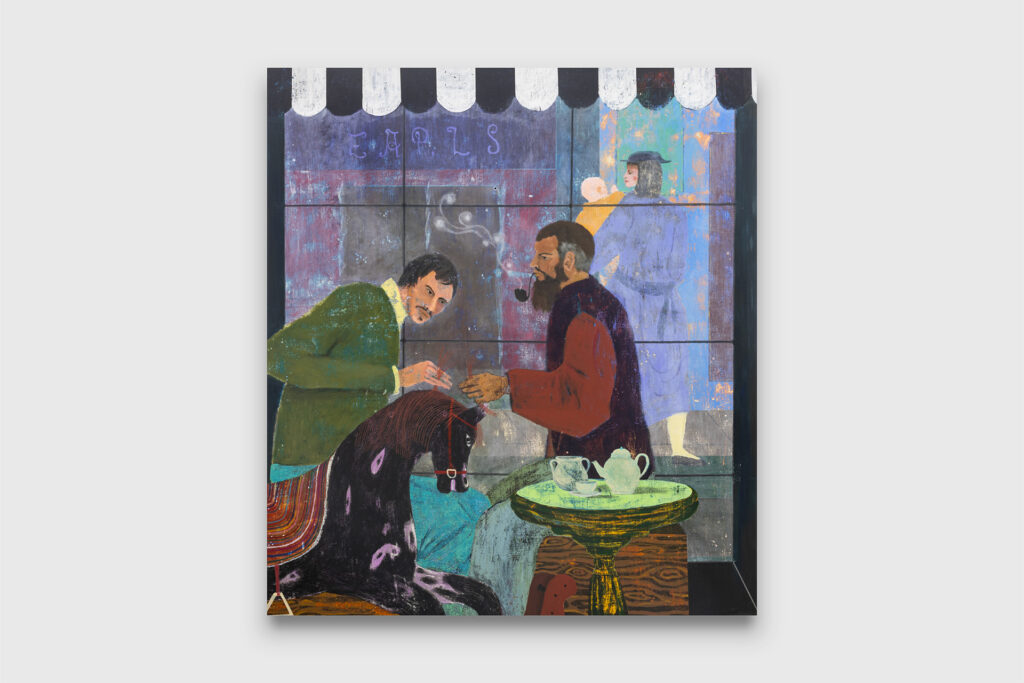

On a final lap around the gallery space, we stop in front of a portrait of two men inside a shopfront, threading what appears to be the mane of a rocking horse. Beyond the windowpanes behind them, a woman wearing a trench coat, also purple, holds a baby. The black-and-white awning of the building feels Parisian, but then again, it’s difficult to place the period of the scene exactly.

“It’s just two guys, smoking ciggies and making a rocking horse,” laughs Williams. “It’s not magical; it’s not Guernica. It’s just this thing that was in my mind. Sometimes, it just needs to be painted.”

All photography courtesy of COMA.

See more of Esquire’s arts coverage:

Inside artist Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran’s eclectic practice

Dylan Mooney takes us inside ‘The Story Of My People’

Behind the scenes of Shaun Daniel Allen’s new solo show

Pro surfer Dion Agius takes us behind the scenes of his first art collection