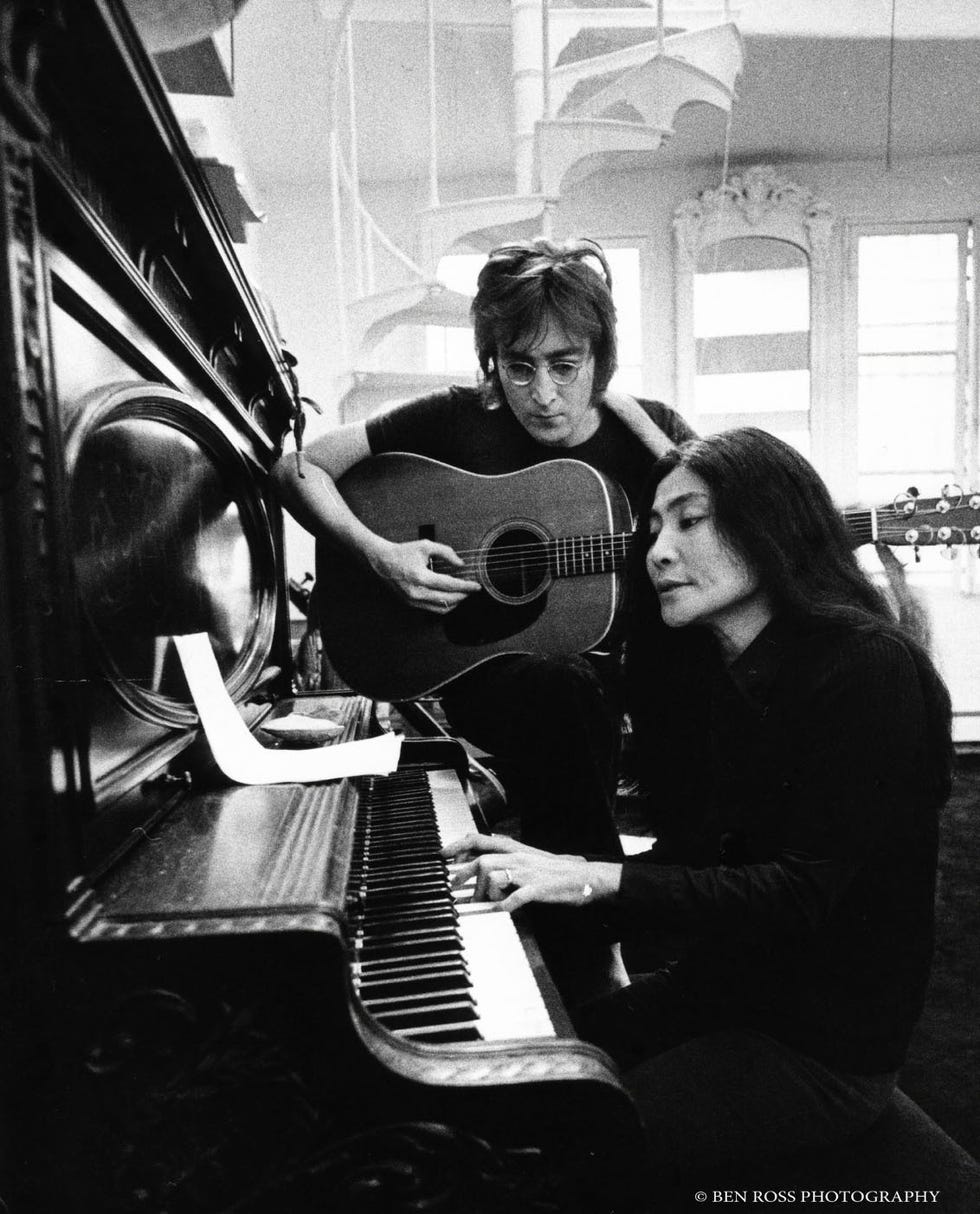

‘One to One’ review: John & Yoko returns to an often forgotten Lennon era

The project marks a chance to reassess, yet again, one of the most consequential and confounding artists, in any medium, of the 20th century

BEATLES SEASON never stops.

In recent months, Paul McCartney closed the Saturday Night Live 50th-anniversary extravaganza with a (somewhat shaky) appearance after sending New York City into a frenzy with three nights of guerilla-style performances at a downtown club. Ringo Starr released Look Up, his best-received album in years, which went to number one on the UK Country and Americana charts and arrived complete with a network-TV special filmed at Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium. And the cast was confirmed for the four feature films coming in 2028 that will make up an all-new Beatles Cinematic Universe.

But lately the spotlight has also been shining on John Lennon. Sixty-five years after the band he started solidified into a steady name and lineup, fifty-five years after they broke up, and forty-five years after his murder, a number of new projects have focused on Lennon’s life and work.

Several recent documentaries have examined specific moments: Revival69 told the story of his last-minute set at the 1969 Toronto Rock and Roll Revival, and Daytime Revolution looked back at the surreal week in 1972 when Lennon and Yoko Ono cohosted the definitively middle-of-the-road Mike Douglas Show. This week, the most ambitious of these projects comes out in One to One: John & Yoko. Codirected by Oscar winner Kevin Macdonald and Sam Rice-Edwards, it examines the period from 1971 to 1973 when Lennon and Ono first moved to New York City, culminating in the one and only full-length concert of Lennon’s solo career. Alongside two major new books that explore his relationships with his two closest collaborators – Ian Leslie’s John & Paul: A Love Story in Songs and David Sheff’s Yoko – this moment is a chance to reassess, yet again, one of the most consequential and confounding artists, in any medium, of the 20th century.

Related: The Beatles will never die. Is that a problem?

“I don’t want to recreate the past, I want to be me now,” says Lennon at one point in the film, which was certainly sincere but also something he claimed repeatedly, at regular intervals. The guy had more eras than Taylor Swift and was always susceptible to a new cause or charismatic leader – drugs, meditation, Primal Scream therapy, macrobiotic food, and conceptual art all defined distinct periods of Lennon’s life.

In the chapter covered in One to One, radical politics is the driving force. “I’m still an artist,” he says, “but a revolutionary artist.” Though John and Yoko first came to the U.S. to locate her daughter, Kyoko, who had been taken by Ono’s ex-husband Tony Cox, they very quickly fell in with figures like Jerry Rubin, cofounder of the Yippies, and underground folk freak David Peel.

It also marked a rising feminist consciousness for him in keeping with the “women’s lib” movement; we see film of Lennon accompanying Ono to the First International Feminist Planning Conference at Harvard as she speaks about how “the whole society wished me dead.”

It was a time of turmoil and paranoia, from the Attica prison riot to the fight for Irish liberation to the later stages of the disintegrating Vietnam War, all culminating in the Watergate hearings (which Lennon and Ono attended). Soon after their arrival in New York, they were off to Michigan to appear at a rally for White Panther activist John Sinclair, who had been jailed for selling two joints to an undercover cop. Two days after the event, Sinclair was freed – and Lennon’s telephone was being tapped (presumably these government tapes are the source of the phone conversations heard throughout the film).

It’s a well-documented but often overlooked phase. When we think of John Lennon in New York, it’s almost invariably his years at the Dakota, raising son Sean and quietly circulating on the city streets before returning to music with the Double Fantasy album in 1980. During these early ’70s years, though, Lennon and Ono lived in a simple ground-level apartment in the West Village (which is re-created meticulously in One to One), where the most notable features were a huge bed and a television that was constantly on.

“I just like TV,” says Lennon. “For me, it replaced the fireplace.” The directors insightfully – if sometimes intrusively – use the perpetual flow of clashing images as a running commentary and theme, juxtaposing the consumerism, information, politics, and abstract imagery flooding Lennon’s thoughts.

If there’s a reason this period is forgotten, it’s because the music Lennon was making at the time is eminently forgettable. The frenetic activism and nonstop input resulted in songs that were closer to journalism than to art, documenting his experiences and opinions in 1972’s Some Time in New York City. So topical it was almost instantly dated, it’s one of rock’s great disasters: Where his previous album, Imagine, hit number one on the U.S. charts, STINYC crawled only to number 48 (complicated by the fact that the lead single was the well-intentioned-at-the-time, impossible-to-imagine-today “Woman is the N****r of the World,” which is also reportedly the reason the album has not been given the deluxe reissue treatment the rest of Lennon’s catalog has gotten).

The documentary chronicles the rise and fall of a “Free the People” tour that would, among other things, raise money to bail out prisoners in each city they played. But as Lennon and Ono sensed that Rubin and the other organisers were leaning into the potential for street violence, especially at the 1972 Republican National Convention, they bailed out – and then, in an unlikely triumph, found another cause to champion.

The omnipresent TV delivered a special investigation by a young reporter named Geraldo Rivera about the horrifying conditions at the Willowbrook State School for Retarded Children. Lennon and Ono chased down Rivera and committed to a benefit concert at Madison Square Garden; they ended up playing two shows (billed as “One to One” and featuring guests including Stevie Wonder and Roberta Flack) on August 30, 1972 – the only time Lennon ever played a complete concert after the Beatles stopped touring in 1966, including his only live performances of songs like “Come Together” and “Instant Karma.”

The concert is scattered throughout One to One, sometimes crosscut with news footage that’s a bit heavy-handed (clips of Richard Nixon as Lennon sings “Hound Dog”). The material has been released before, on the 1986 album and home video Live in New York City, but it’s generally been dismissed by fans and critics, for the sense that Lennon’s voice wasn’t in great shape and that the backing group, local bar band Elephant’s Memory, was sloppy and underwhelming. The remix in the film, though, is a revelation, with a dramatically improved sound that’s far more confident and convincing.

There’s touching footage of the Willowbrook families having a picnic in Central Park as Lennon sings “Imagine,” and it brings home that after all this casting around for a mission, John and Yoko found something finite, concrete, and close to home that made an actual difference. “These children are almost symbolic of all the pain on earth,” he says. “It’s a start. Where do you start?”

In his perceptive John & Paul, Ian Leslie writes that “in the 1970s, John was the hero the world wanted: ostentatiously anti-establishment, charismatically tormented – a figure who matched not just the moment, but also much older ideas of genius.” But One to One reminds us that for part of that decade, the world didn’t really care that much about Lennon, and he was mostly creating problems for himself. And things would get worse (the drunken “Lost Weekend” period in Los Angeles, a long deportation fight with the government) before they got better.

The months captured in the documentary are hardly John Lennon’s greatest creative era, but the velocity with which he’s moving, the excitement and energy he’s feeling, and the bravery of his personal journey are an inspiration. He’s under no illusion that he’s found the answers – “usually a warning light comes on when I’m becoming something I don’t want to be,” he says at one point – but he never stopped searching.

“The hardest thing to face,” Lennon concludes, “is yourself.”

This story originally appeared on Esquire US.

Related:

Everything you need to know about all four of the ‘The Beatles’ movies