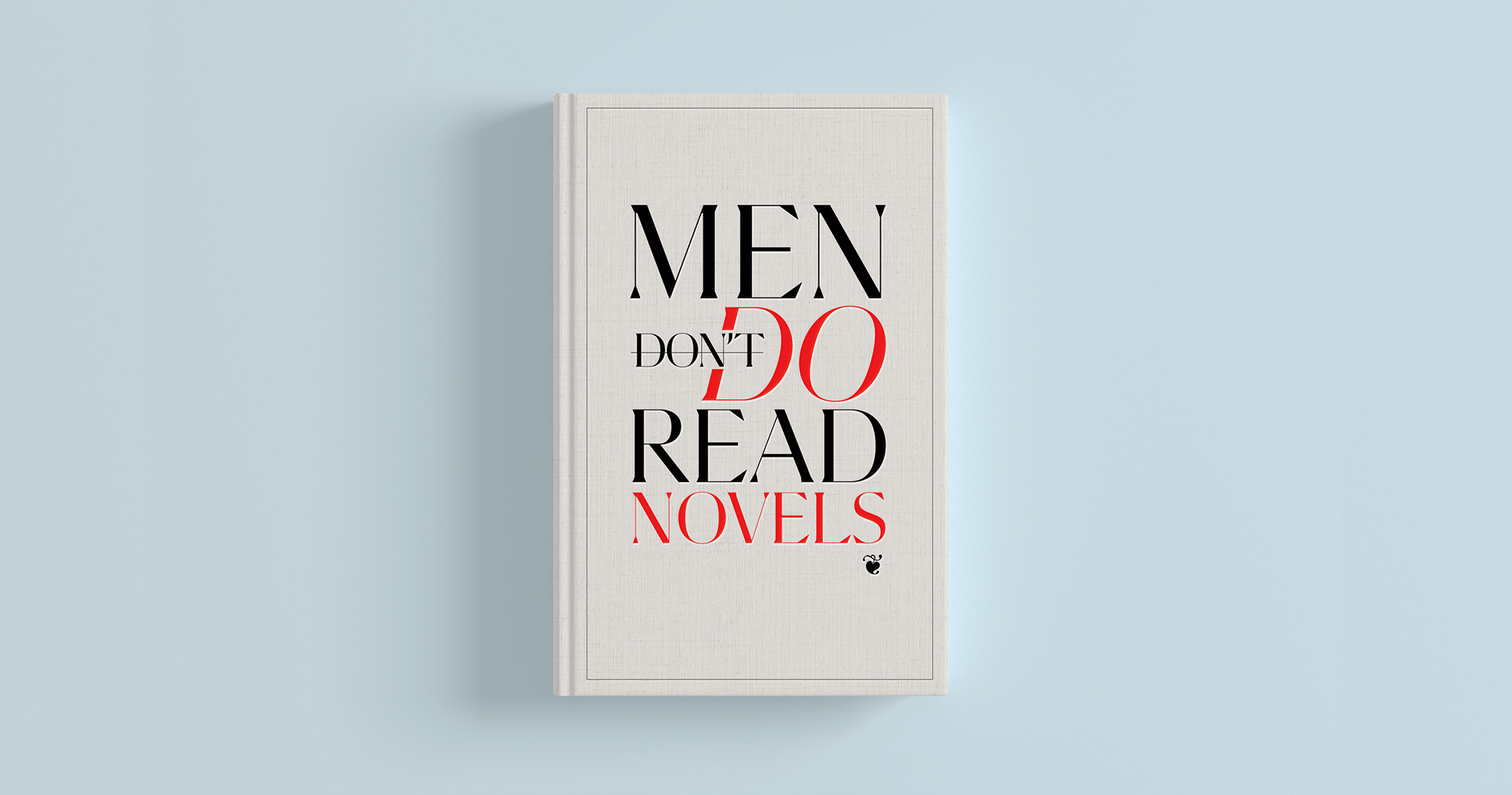

Why men should read literary fiction

In a pair of bold new novels David Szalay and Charlie Porter take on modern masculinity

WRITING IN THE New Statesman recently, Jason Cowley lamented the sharp decline in prominence and influence of the literary novel over the past decades. He drew a comparison between the works of fiction shortlisted for the most recent Booker Prize, and those competing in 1997, when he was one of the judges, and Arundhati Roy won for her international bestseller, The God of Small Things. That was a time, Cowley felt, when literary novels were more urgent, more engaged with contemporary culture and society, and as a result more likely to attract a wide readership.

“[Now],” he wrote, “as I travel in and out of London most days, looking at people looking at their phones or watching video clips or movies, I am struck by the total irrelevance of the literary novel – certainly among men, especially younger men.”

He’s not wrong about that. As ever, the law of supply and demand applies. It is axiomatic that the fewer young men who buy and read literary novels, so the fewer literary novels will be published that might appeal to young men. The days that Cowley yearns for when the new Ian McEwan might be discussed over a pint with the same passionate intensity as politics or football, are so remote that even the most gifted writer of historical fiction might struggle to summon them for today’s reader.

But terrific literary novels are still being published that men, even young men – especially young men – should seek out. Because a good novel does something that a TV show or a podcast or a TikTok video never can. It takes you inside the thoughts and feelings of another person, gives you access to his or her hopes, fears, doubts, dreams and desires. A fully realised fictional character is, in this way, more real than even your closest friend. Hell, he or she is more real than you.

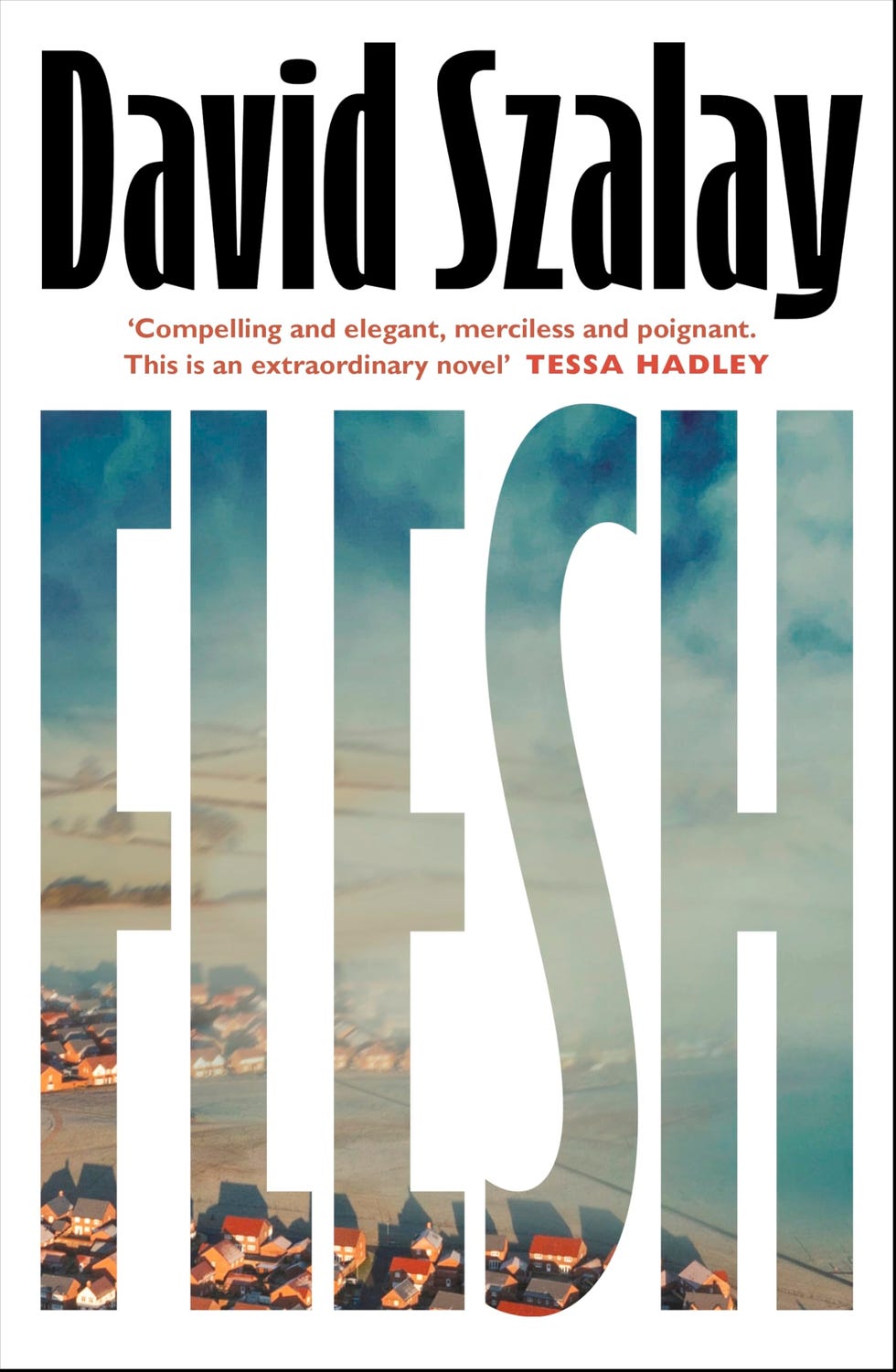

Two novels have been published in the past few weeks that I think young men (and older men) would get something from: David Szalay’s Flesh and Charlie Porter’s Nova Scotia House.

Szalay’s book we have already championed in Esquire. He is for my money the shrewdest writer on contemporary masculinity we have. Also, the funniest. Flesh follows its protagonist, István, from a Hungarian boyhood characterised by isolation, hardship, and misunderstanding to a London adulthood characterised by isolation, luxury, and misunderstanding. István endures violence, imprisonment, quite a lot of rather joyless sex, failures to connect, enormous wealth, and switchback turns of fortune. Written in Szalay’s boldly spare style, Flesh is as potent a portrait of the myth of free will as I can remember. It’s also a page-turner. You’ll race through it.

Unlike Szalay, Charlie Porter is a debut novelist. A former staffer at both Esquire and GQ, where I worked alongside him twenty years ago, he went on to a career as a fashion journalist before switching to books, publishing stylish works on fashion and art.

Nova Scotia House has a distinctive style, a sort of neo-modernist first-person stream of consciousness. (Porter has written before about the Bloomsbury group; he knows his Virginia Woolf.) I was uncertain about this for the first page or two but soon succumbed. It is a beautiful book, angry and elegiac, hopeful and romantic, and very moving, in which the narrator, 48-year-old Johnny, looks back on his relationship with the love of his life, Jerry, long since dead.

Johnny and Jerry met in the early 1990s, when Johnny was 19, lost and lonely, and the charismatic Jerry was 45. In telling their story, set in a desolate, unnamed London, Porter summons the horror of the AIDS crisis — and shows that for many that crisis has not ended — and the fear and repression experienced by gay men, in visceral scenes of fear and suffering. But he also hymns the glories of queer life, pubs and clubs, sex and friendship, and a militant refusal to conform to the suffocating strictures of straight society.

This is muscular writing, and a reminder that when it’s done well a literary novel can take you to places you’ve never been and wouldn’t otherwise be able to go. Queer magic, as Jerry would say.

This story originally appeared on Esquire UK.

Related: